In my second-last post, I discussed the recent controversy over the term "evidence-based". It was popularized through evidence-based medicine, an enormously influential movement spearheaded in the early 1990's by epidemiologists at McMaster University (see accompanying picture of main campus). It certainly sounds reasonable to suggest that medicine (or healthcare more broadly, or education, or policy ...) should be evidence-based, but what does it mean? Here, repeating from my last post, is probably the best known definition of evidence-based medicine:

"the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients."Clearly the first step in making sense of this definition is to sort out what evidence is.

But is it really important to define evidence? Isn't it just semantics? Well, I think it does matter—for two reasons. First, there's been a widespread push for evidence-based practice and policy. Funding bodies and organizations are giving priority to "evidence-based" approaches and initiatives, and that can have a substantial impact on what research gets done and what practices and policies get implemented. Second, if evidence is not clearly defined, how can we define what "current best evidence" is?

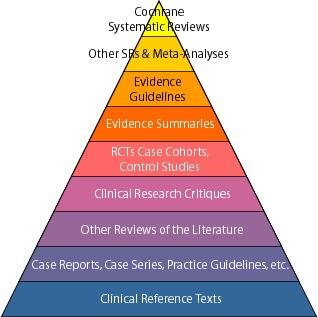

The attempt to delineate different "levels of evidence" has been an ongoing preoccupation of evidence-based medicine. The notion is that some study designs provide more valid or reliable evidence than others, and that there is a "hierarchy of evidence", often depicted as a pyramid such as this one:

(source)

(source)It's not hard to see why this engenders so much heated debate. For example in the figure above, "in vitro ('test tube') research" ranks below "ideas, editorials, opinions"! But this is only one of several such evidence hierarchies, which have notable differences.

For example, the figure below makes no mention at all of benchtop science, and puts "evidence guidelines" higher than randomized controlled trials (RCTs):

(source)

(source)As with the previous pyramid, meta-analyses and systematic reviews appear, but here Cochrane systematic reviews are judged best of all ("the 'Gold Standard' for high-quality systematic reviews").

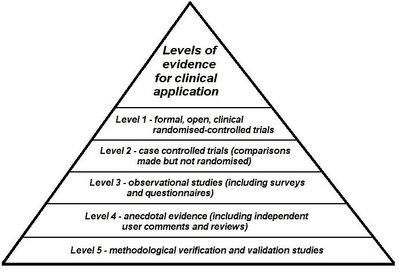

Here's one more pyramid, which doesn't include systematic reviews, but does include anecdotal evidence:

(source)

(source)There are lots of other evidence hierarchies, for example the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence, which makes distinctions according to what the evidence is about (e.g. therapy versus diagnosis).

Distilling the different types of "evidence" from these hierarchies suggests that, according to the authors, evidence may include various types of: (1) empirical studies, (2) summaries of empirical studies, and (3) opinions (hmmm ...). But it's certainly clear that there isn't complete consensus on exactly what qualifies in each of these categories, nor on the rankings.

Perhaps all these pyramids haven't been built on the strongest foundations?

No comments:

Post a Comment