Missing values are the bane of the applied statistician. They haunt our data sets, invisible specters lurking malevolently.

The missing value is like the evil twin of zero. The introduction of a symbol representing "nothing" was a revolutionary development in mathematics. The arithmetic properties of zero are straightforward and universally understood (except perhaps when it comes to division by zero, a rather upsetting idea). In comparison, the missing value has no membership in the club of numbers, and its properties are shrouded in mystery. The missing value was a pariah until statisticians reluctantly took it in—

someone had to. And it's an ill-behaved tenant, popping in and out unexpectedly, sometimes masquerading as zero, sometimes carrying important messages—always a source of mischief.

... symbolizing nothingA variety of different symbols are used to represent missing values. The statistical software packages SAS and SPSS, for example, use a dot. The fact that it's almost invisible is oddly fitting. Other software uses NA or N/A—but does that mean "not available" or "not applicable"? These are, after all, two very different situations. The

IEEE floating point standard includes

NaN, meaning "not a number" (for example 0/0 is not a number). In spreadsheets, a missing value is simply an empty cell (but in Excel, at least, invalid calculations result in special types of missing values—for example 0/0 results in "#DIV/0!"). Dates and times can also be missing, as can character string variables.

Logical expressions, such as "X > 0" (which can either be TRUE or FALSE), are an interesting special case. If X is missing, then the value of the expression itself is missing. Suppose Y=5. If X is missing, what is the value of the expression "(X > 0) AND (Y > 0)"? Well, we can't say, because we need to know the values of both X and of Y to determine the result. So the value of "(X > 0) AND (Y > 0)" is missing. How about "(X > 0) OR (Y > 0)"? In this case, the answer is TRUE. It is enough to know that Y is positive to answer the question, regardless of the value of X. (There's also a logical operation called exclusive-OR, denoted XOR, which means "one or the other is true, but not both". You'd need to know both values in that case.)

Even though the rules above seem straightforward, great care must still be taken in ensuring that calculations are handling missing values appropriately. That's because in reality there are any number of different kinds of missing values. Suppose, for example, that as part of a clinical study of neurotoxic effects of chemotherapy agents, IQ is measured. What does a missing value in the data set mean? Perhaps the patient wasn't available on the day the measurement took place. Or perhaps they died. Or perhaps their cognitive disability was so severe that the test couldn't be administered. In the last two cases, the missingness might well be related to the neurotoxic effect of interest. This is known as

informative missingness. Statisticians also distinguish the case where values are "missing at random" versus "missing completely at random". The latter is the best we can hope for—but it's often wishful thinking.

Something for nothingOne potential solution to the problem of missing values is

imputation, that is filling in values ... somehow. One approach is

mean imputation in which the mean of the values that are

not missing is substituted for any missing values. Seems reasonable, except that it effectively reduces variability, which can seriously distort inferences. A variety of other

imputation methods have been proposed, the most sophisticated of which,

multiple imputation, allows for valid variance estimates

provided a number of assumptions hold. The bottom line is there are no easy solutions: you can't get something for nothing ... for nothing.

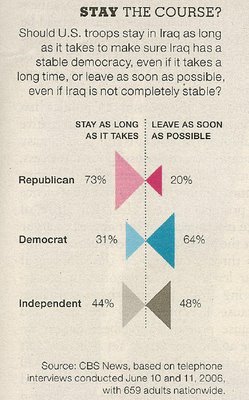

Too much of nothingThe really unfortunate thing is that missing values are often the result of bad design. Perhaps the most common instance of this is surveys. Most surveys are

too long! This creates at least three problems. The first is non-response (which is missing values writ large). While I might be willing to spend 30 seconds answering a questionnaire, I'd be much less interested in spending 10 minutes. The second problem is that even if I do answer the questionnaire, I may get tired and skip some questions (or perhaps only get part way through), or take less care in answering. The third problem is that long surveys also tend to be badly designed. There's a simple explanation for this: when there are a small number of questions, great care can be taken to get them right; typically when there are a large number of questions, less effort is put into designing each individual question. "Surveybloat" is ubiquitous and wasteful, often the product of design-by-committee. The desire to add "just one more question" is just too strong and the consequences are apparently too intangible (despite being utterly predictable). I would say that most surveys are at the very least

twice as long as they ought to be.

In medical research, the

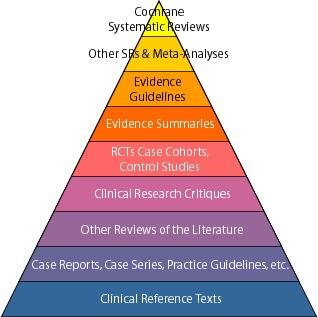

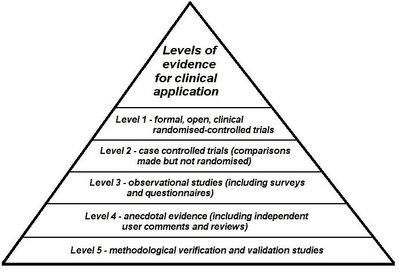

randomized controlled trial is considered to be the "gold standard" of evidence. By randomly assigning an experimental intervention to some patients and a control (for example, standard care) to other patients, the effect of the experimental intervention can be reliably assessed. Because of the random allocation, the two groups of patients are unlikely to be very different beforehand. This is a tremendous advantage because it permits

fair comparisons. But everything hinges on being able to assess the outcomes for

all patients, and this is surprisingly difficult to do. Patients die or drop out of studies (due to side effects of the intervention?); forms are sometimes lost or not completed properly; it's not always possible to obtain follow-up measurements—the sources of missing values are almost endless. But each missing value weakens the study.

If this is a problem with prospective studies, in which patients are followed forward in time and pre-planned measurements are conducted, imagine the difficulties with retrospective studies, for example reviews of medical charts. Missing values are sometimes so prevalent that data sets resemble Swiss cheese. In such cases, how confident can we really be in the study findings?

Learning nothingMost children learn about zero even before they start school. But who learns about missing values? University-level statistics courses cover

t-tests, chi-square tests, analysis of variance, linear regression ... (How much of any of this is retained by most students is another question.) It's only in advanced courses that any mention is made of missing values. So graduate students in statistics (and perhaps students in a few other disciplines) learn about missing values; but even then, it's usually from a rather theoretical perspective. In day-to-day data analysis, missing values are rife. I would hazard a guess that of all the

p-values reported in scientific publications, at least half the time there were missing values in the corresponding data, and they were simply ignored. In scientific publications, missing values are routinely swept under the carpet.

Missing values are a bit of a dirty secret in science. Because they are rarely mentioned in science education, it's not surprising that they are often overlooked in practice. This is terribly damaging—regardless of whether it's due to ignorance, dishonesty, or wishful thinking.

Nihil obstatIn some cases, missing values may just be an irritation with little consequence other than a reduction in sample size. It would be lovely if that were always the case, but it simply isn't. We ignore missing values at our peril.

———

Addendum (22June2006):In my post I discussed how logical expressions are affected by missing values. The difference between a value that is

not available and one that is

not applicable has an interesting effect here. Suppose that following an initial assessment of a patient, a clinic administers a single-sheet questionnaire each time the patient returns. One of the questions is:

Since your last visit, have you experienced such-and-such symptom?

It might be of interest to know what proportion of patients have ever answered yes. Suppose that patients returned to the clinic up to three times. A logical expression to represent whether each patient had ever experienced the symptom would be:

symptom = v1 OR v2 OR v3

where v1 is TRUE if the patient reported the symptom on the first return visit, and likewise for v2 and v3. Suppose that a particular patient returned to the clinic three times, and answered "no" the first two times, but the questionnaire sheet for that patient's third visit was misplaced. Then v1=FALSE, v2=FALSE, and v3 is missing (

not available). Following the rules that I discussed earlier for logic with missing values (these are rules used in SPSS and R, and I suspect in most other statistical packages), the value of the logical expression would be missing, which makes sense: we unfortunately don't know if the patient ever reported experiencing the symptom.

Suppose that another patient only returned to the clinic twice, also answering "no" on both visits. Then again v1=FALSE, v2=FALSE, and v3 is missing (

not applicable, since there

was no third visit). Blindly applying the rules, the value of the logical expression would again be missing. But this time, it's incorrect: we know that this patient

never reported experiencing the symptom.

This is one of the justifications for my statement that "Even though the rules above seem straightforward, great care must still be taken in ensuring that calculations are handling missing values appropriately."